Following the “paradigm-shifting” Los Angeles wildfires in January, the 2024-2025 wildfire season will be remembered as a turning point for the insurance industry, and a warning that “wildfire is no longer a seasonal or rural phenomenon,” a new outlook asserts.

The rest of 2025 poses severe wildfire risk in numerous states thanks to developing drought conditions, including high risk in wildfire-prone California, according to a report from ZeztyAI.

The L.A. wildfires killed 29 people, and damaged or destroyed thousands of properties. The fallout of the fires included large losses for major California insurers, including State Farm. The carrier is asking the California Department of Insurance to approve a large rate increase. According to the California Department of Insurance, 37,749 claims have been filed related to the fires and $12.1 billion has been paid out.

However, the wildfire perils weren’t only in California.

Related: Homeowners Suing USAA and AAA Insurers Over LA Wildfires

“From New Mexico, where one of the state’s most destructive wildfires validated early high-risk forecasts, to blazes in the Midwest and Southeast, the 2024 season revealed wildfire’s expanding geographic footprint, relentless pace, and increasingly unpredictable behavior,” the report stated. “For insurance carriers, it exposed the limits of legacy models still tied to historical fire perimeters or broad geographic zones, and accelerated adoption of next-generation tools that assess parcel-level vulnerability—including structural features, defensible space, and vegetation overhang.”

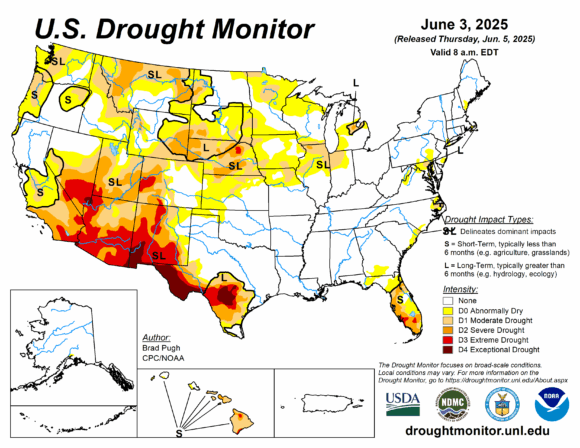

The rest of the year is shaping up to be more volatile following a moderate 2024 wildfire season. Severe drought conditions are expected to return and spread across the country, with intensified dryness in the Southwest and deep into the Northern Rockies and the Plains, according to the report.

“Heavy rains in California, Oregon, and Washington during the past two years have driven significant vegetation growth. If heat and dryness persist into late summer as forecasted, these areas could once again become highly combustible,” the report states. “This familiar pattern, where wet years boost fuel loads that turn dangerous when conditions shift, remains a long-term driver of wildfire risk in these historically vulnerable states.”

Related: Bill to Address California Wildfire And Insurance Crises Moving Through Legislature

The report notes that states like Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Colorado remain in multi-year droughts, while Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota are emerging as new high-risk zones due to a dry, snow-starved winter and unusually warm spring. Drought signals are also coming out of Texas and Florida, according to the report.

The report also touches on how new state rules and laws are reshaping how insurers are assessing and communicating risk:

- In late 2024, the California Department of Insurance finalized its Sustainable Insurance Strategy, a reform to stabilize the state’s insurance market. Central to the strategy is the approval of forward-looking catastrophe models in rate filings—allowing insurers to price wildfire risk based on future exposure rather than past losses.

- In 2025, Colorado enacted House Bill 25-1182, establishing a new benchmark for transparency in wildfire risk modeling. The law applies to all admitted carriers and the FAIR Plan. It requires insurers to disclose how wildfire models impact rates, recognize both property- and community-level mitigation efforts, notify policyholders annually of their risk scores and discounts and provide an appeals process for disputed scores.

- In 2024, Washington adopted new regulations aimed at improving transparency around insurance premium increases. Insurers are required to notify policyholders that they may request a written explanation for any increase in their homeowners or auto insurance premiums. Upon request, carriers must provide a rationale within 20 days.

- In April, Oregon passed Senate Bill 83, repealing the state’s mandatory wildfire hazard map following sustained public opposition. The original map had classified properties into risk zones that triggered defensible space requirements and stricter building codes—measures that some property owners argued were based on incomplete or inaccurate data and had unintended consequences on insurance availability and property values.